As illustrated at beginning of this chapter, one role of a .NET compiler is to generate metadata descriptions for all defined and referenced types. In addition to this standard metadata contained within any assembly, the .NET platform provides a way for programmers to embed additional metadata into an assembly using attributes. In a nutshell, attributes are nothing more than code annotations that can be applied to a given type (class, interface, structure, etc.), member (property, method, etc.), assembly, or module.

The idea of annotating code using attributes is not new. COM IDL provided numerous predefined attributes that allowed developers to describe the types contained within a given COM server. However, COM attributes were little more than a set of keywords. If a COM developer needed to create a custom attribute, he or she could do so, but it was referenced in code by a 128-bit number (GUID), which was cumbersome at best.

.NET attributes are class types that extend the abstract System.Attribute base class. As you explore the .NET namespaces, you will find many predefined attributes that you are able to make use of in your applications. Furthermore, you are free to build custom attributes to further qualify the behavior of your types by creating a new type deriving from Attribute.

The .NET base class library provides a number of attributes in various namespaces. Table 15-3 gives a snapshot of some—but by absolutely no means all—predefined attributes.

Table 15-3. A Tiny Sampling of Predefined Attributes

| Attribute | Meaning in Life |

|---|---|

| [CLSCompliant] | Enforces the annotated item to conform to the rules of the Common Language Specification (CLS). Recall that CLS-compliant types are guaranteed to be used seamlessly across all .NET programming languages. |

| [DllImport] | Allows .NET code to make calls to any unmanaged C- or C++-based code library, including the API of the underlying operating system. Do note that [DllImport] is not used when communicating with COM-based software. |

| [Obsolete] | Marks a deprecated type or member. If other programmers attempt to use such an item, they will receive a compiler warning describing the error of their ways. |

| [Serializable] | Marks a class or structure as being “serializable,” meaning it is able to persist its current state into a stream. |

| [NonSerialized] | Specifies that a given field in a class or structure should not be persisted during the serialization process. |

| [WebMethod] | Marks a method as being invokable via HTTP requests and instructs the CLR to serialize the method return value as XML. |

Understand that when you apply attributes in your code, the embedded metadata is essentially useless until another piece of software explicitly reflects over the information. If this is not the case, the blurb of metadata embedded within the assembly is ignored and completely harmless.

As you would guess, the .NET 4.0 Framework SDK ships with numerous utilities that are indeed on the lookout for various attributes. The C# compiler (csc.exe) itself has been preprogrammed to discover the presence of various attributes during the compilation cycle. For example, if the C# compiler encounters the [CLSCompliant] attribute, it will automatically check the attributed item to ensure it is exposing only CLS-compliant constructs. By way of another example, if the C# compiler discovers an item attributed with the [Obsolete] attribute, it will display a compiler warning in the Visual Studio 2010 Error List window.

In addition to development tools, numerous methods in the .NET base class libraries are preprogrammed to reflect over specific attributes. For example, if you wish to persist the state of an object to file, all you are required to do is annotate your class or structure with the [Serializable] attribute. If the Serialize() method of the BinaryFormatter class encounters this attribute, the object is automatically persisted to file in a compact binary format.

The .NET CLR is also on the prowl for the presence of certain attributes. One famous .NET attribute is [WebMethod], used to build XML web services using ASP.NET. If you wish to expose a method via HTTP requests and automatically encode the method return value as XML, simply apply [WebMethod] to the method and the CLR handles the details. Beyond web service development, attributes are critical to the operation of the .NET security system, Windows Communication Foundation, and COM/.NET interoperability (and so on).

Finally, you are free to build applications that are programmed to reflect over your own custom attributes as well as any attribute in the .NET base class libraries. By doing so, you are essentially able to create a set of “keywords” that are understood by a specific set of assemblies.

To illustrate the process of applying attributes in C#, create a new Console Application named ApplyingAttributes. Assume you wish to build a class named Motorcycle that can be persisted in a binary format. To do so, simply apply the [Serializable] attribute to the class definition. If you have a field that should not be persisted, you may apply the [NonSerialized] attribute:

// This class can be saved to disk. [Serializable] public class Motorcycle { // However this field will not be persisted. [NonSerialized] float weightOfCurrentPassengers; // These fields are still serializable. bool hasRadioSystem; bool hasHeadSet; bool hasSissyBar; }

Note An attribute applies to the “very next” item. For example, the only nonserialized field of the Motorcycle class is weightOfCurrentPassengers. The remaining fields are serializable given that the entire class has been annotated with [Serializable].

At this point, don’t concern yourself with the actual process of object serialization (Chapter 20 examines the details). Just notice that when you wish to apply an attribute, the name of the attribute is sandwiched between square brackets.

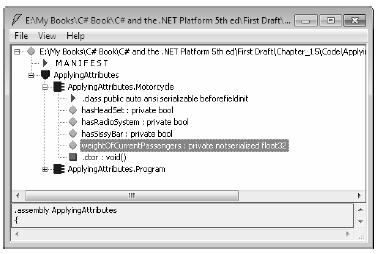

Once this class has been compiled, you can view the extra metadata using ildasm.exe. Notice that these attributes are recorded using the serializable token (see the red triangle immediately inside the Motorcycle class) and the notserialized token (on the weightOfCurrentPassengers field; see Figure 15-3).

Figure 15-3 Attributes shown in ildasm.exe

As you might guess, a single item can be attributed with multiple attributes. Assume you have a legacy C# class type (HorseAndBuggy) that was marked as serializable, but is now considered obsolete for current development. Rather than deleting the class definition from your code base (and risk breaking existing software), you can mark the class with the [Obsolete] attribute. To apply multiple attributes to a single item, simply use a comma-delimited list:

[Serializable, Obsolete("Use another vehicle!")]

public class HorseAndBuggy

{

// ...

}

As an alternative, you can also apply multiple attributes on a single item by stacking each attribute as follows (the end result is identical):

[Serializable]

[Obsolete("Use another vehicle!")]

public class HorseAndBuggy

{

// ...

}

If you were consulting the .NET Framework 4.0 SDK documentation, you may have noticed that the actual class name of the [Obsolete] attribute is ObsoleteAttribute, not Obsolete. As a naming convention, all .NET attributes (including custom attributes you may create yourself) are suffixed with the Attribute token. However, to simplify the process of applying attributes, the C# language does not require you to type in the Attribute suffix. Given this, the following iteration of the HorseAndBuggy type is identical to the previous (it just involves a few more keystrokes):

[SerializableAttribute] [ObsoleteAttribute("Use another vehicle!")] public class HorseAndBuggy { // ... }

Be aware that this is a courtesy provided by C#. Not all .NET-enabled languages support this shorthand attribute syntax.

Notice that the [Obsolete] attribute is able to accept what appears to be a constructor parameter. If you view the formal definition of the [Obsolete] attribute using the Code Definition window (which can be opened using the View menu of Visual Studio 2010), you will find that this class indeed provides a constructor receiving a System.String:

public sealed class ObsoleteAttribute : Attribute { public ObsoleteAttribute(string message, bool error); public ObsoleteAttribute(string message); public ObsoleteAttribute(); public bool IsError { get; } public string Message { get; } }

Understand that when you supply constructor parameters to an attribute, the attribute is not allocated into memory until the parameters are reflected upon by another type or an external tool. The string data defined at the attribute level is simply stored within the assembly as a blurb of metadata.

Now that HorseAndBuggy has been marked as obsolete, if you were to allocate an instance of this type:

static void Main(string[] args) { HorseAndBuggy mule = new HorseAndBuggy(); }

you would find that the supplied string data is extracted and displayed within the Error List window of Visual Studio 2010, as well as one the offending line of code when you hover your mouse cursor above the obsolete type (see Figure 15-4).

Figure 15-4 Attributes in action

In this case, the “other piece of software” that is reflecting on the [Obsolete] attribute is the C# compiler. Hopefully, at this point, you should understand the following key points regarding .NET attributes:

Next up, let’s examine how you can build your own custom attributes and a piece of custom software that reflects over the embedded metadata.

Source Code The ApplyingAttributes project is included in the Chapter 15 subdirectory.